|

| Neither jaws nor web to help, just Gestalt |

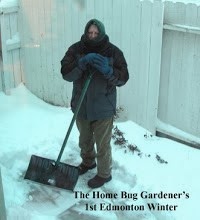

The image above has appeared before at the Home Bug Garden, but never in a starring role (and once with the name misspelled). I like to think of this as a species of

Tetragnatha - a Long-jawed Orb Weaver - and since neither the critical morphological character (the long 'jaws') nor a useful behaviour character (webs horizontal to the ground) are visible, it seems a perfect introduction to another Adventure in Spider Misidentification. Might as well jump in at the deep end: I'm guessing this is

Tetragnatha laboriosa Hentz, 1850, the Silver Long-jawed Orb Weaver.

|

| Horizontal web, often near or above water |

I'm not being entirely arbitrary in my identification. Species of

Tetragnatha are elongate and I have seen long 'jaws' on close inspection of other specimens. Also, the webs are definitely horizontal and often around the pond - sometimes strung from sedges over the water.

Tetragnatha laboriosa occurs in Canada and the images at BugGuide look more or less the same. Isn't that enough?

|

| Whatever this spider may be, there is one less aphid in the HBG |

Well, no. A composite of characters from a variety of individuals is no way to come up with a reliable identification. Best is a specimen, microscope, and key. Second best a really good set of pictures showing all the characters needed. I don't have any of those and I'm relying on something I learned long ago, in another land: the Gestalt of a

Tetragnatha. That and an 'educated' guess on what species this might be. But BugGuide doesn't have pictures of all the species of

Tetragnatha that occur in Canada, more than half of what they do have are unidentified images, and ominously one of these sets is labelled

Alberta and Saskatchewan.

|

| Tetragnatha maybe, species unknown |

Well there's nothing wrong in being wrong, just in refusing to admit it. So, I'm pretty sure this spider belongs to Tetragnathidae and probably to

Tetragnatha, but I think I'm going to have to collect a few and do some hard work at the microscope if I want to get any further.