|

| A Cowslip or Oxslip - a hardy and typical wild primrose |

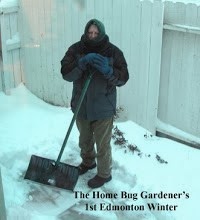

This Christmas is a working holiday at the Home Bug Garden.

When I’m not shoveling snow off the walkways or raking it off the roof, I’m

plunked down in front of the computer plugging away at the second edition of a

book. Unfortunately, the latter is proving to be more of a chore than expected

(a lot of new science has been published in the 13 years since the first

edition), and since there is only a skiff of new snow to sweep away this

morning, I need something else to do as a break.

|

| Primula veris or 'Little First of the Spring' |

It’s too cold (the predicted high today is -23 C) to go

looking for winter insects, but cold and snow are good motivators for

daydreaming about next spring. The Latin word for spring is ver, from which we get our word ‘vernal’

(as in Vernal Equinox, the next being a very distant 20 March 2013).

|

| Cowslip is a June bloomer here |

Ver is also the

root for one of the Home Bug Garden flower species, Primula veris Linnaeus, 1753. The Latin name means more or less

‘little first flower of the spring’, but in the Home Bug Garden early June is when it appears. Also known as Cowslip or Oxslip, veris is the type species on which the genus Primula is based and Primula

is the type genus on which the Family Primulaceae is based.

|

| Garden primroses come from Cowslip, Common Primrose and others |

The Cowslip is also the very humble base from which many spectacular horticulture varieties have been bred by crossing with Common Primrose (Primula vulgaris) to produce the 'Polyantha' hybrids.

|

| Auricula hybrid primrose |

The Mountain Cowslip (Primula auricula) also seems like a modest beginning for a vast hybrid swarm of form and colour, but the breeding has been going on for centuries.

Even without human intervention, Primula is a very successful genus with more than 400 described species worldwide. Only

20 of these species are native to North America, but four of these grow wild in

Alberta. Mealy Primrose (Primula incana)

is the only one that I have seen – a small, but pretty wildflower that grows in

marshy areas throughout much of central Alberta.

|

| Drumstick Primrose (Primula denticulata) more or less hardy here |

Dwarf Canadian Primrose (Primula mistassinica) and Greenland Primrose (Primula egaliksensis) are restricted to marshy spots in the Rockies and Strict

Primrose (Primula stricta), although Holarctic, is found here only in the Canadian Shield part of extreme northeastern Alberta.

|

| Siberian or Cortusa Primrose (Primula cortusoides) |

Although spectacular, and more or less hardy, the hybrid primroses do tend to be short-lived. We've had better luck with some of the species primroses. Alas not the Orchid Primrose (Primula vialii), it's not quite hardy here and more a biennial than perennial anyway. However, Siberian Primrose (Primula cortusoides) is both hardy and very attractive - much like a wild primrose, but larger.

|

| Siberian Primrose |

'Cortusoides' means 'resembling Cortusa', another of the four genera of Primulaceae in the Home Bug Garden: Primula, Dodecatheon, Androsace, and Cortusa. Apparently the latter was named in honour of a Paduan professor of botany Cortusus. They are commonly called Alpine Bells and I have blogged about them before and have nothing new to add other than the origin of the genus name.

|

| Alpine Bells another striking wildflower from the Primrose family |

I've also blogged briefly about the delightful Pygmyflower Rockjasmine (Androsace

septentrionalis Linnaeus) before, one of three species in the genus that occur in Alberta.

|

| Pygmyflower Rockjasmine, a Primrose family wildflower and weed |

Androsace seems to be from the Greek for 'man + shield', perhaps ‘shield of men’ as Andromeda means ‘ruler of

men’. You may have heard of Andromeda from the galaxy, short-lived TV-series, movie and novel (Andromeda Strain) or Andromeda polifolia L. the Bog Rosemary, but the name goes back to Greek Mythology. Since the Greeks (androsakes)

and Romans (androsaces) fused this name for the

rock-jasmine, though, perhaps we need not delve further.

|

| Eastern Shooting-star Dodecatheon meadia - a primrose in all but name |

Amazingly, though, and in spite of my best intentions, I seem to have never taken time to wax prolix about the Home Bug Garden's Shootingstars! Perhaps this is because I'm a bit embarrassed that our species, Dodecatheon meadia (aka Pride of Ohio, Eastern Shootingstar), is not one of the two species native to Alberta: Dodecatheon conjugens (Bonneville Shootingstar) and Dodecatheon pulchellum (Darkthroat Shootingstar). Both species are broadly distributed in, respectively, grasslands and wet meadows or saline flats, in the southern third of the Province. Although mostly North American, Dodecantheon seems to be another of those ancient words for a flower (in this case Greek).

|

| Russian Blue Potato Flower - not a primrose, but buzz-pollinated |

Although not looking much like a primrose, shootingstars are good Primulaceae and closely related to Primula. They have a variety of more humdrum common names such as Mosquito Bill and Mad Violet that refer to their strange inside-out flowers. There is a method to this madness, though. Shootingstars require a special kind of pollination where a bee hangs onto the anthers (the cone in the middle) and buzzes its wings to shake pollen out of the pore at the tip of each anther. Some of our common crops in the Solanaceae such as potato, tomato, and eggplant also are buzz-pollinated and only certain bees (mostly bumblebees and leaf-cutter bees) are smart enough to learn how to buzz. I suspect that having the petals out of the way helps.

|

| Mad Violet, Mosquito Bill or Shootingstar, a Primrose for all of that |

In Australian, what I’ve been doing is officially

known as ‘bludging’ (evading work), but I prefer to think of it as toning up my

botanical skills. In any case, it is Christmas Eve and wishing all my readers Merry Christmas or Happy Whatever Holiday You May Celebrate seems in order. Now, alas, it is time to go back to work.